The Conservatives are proposing a form of free market education, based largely according to them on the Swedish (and also American and Canadian) model of the last 20 years. The problem is, there's no convincing argument what they're doing is constructive.

They want to allow parents to effectively choose which school they want their portion of the schools' budget to go to, in essence forcing schools to compete for students.

There are two main problems with the Conservatives' position, perhaps symbolic of the current trends in politics - firstly, their policy is not right-wing enough, because it fails to allows schools to turn a profit (as Swedish schools can) and hence will likely lead to charitable institutions and small collabratives setting up minor that have little impact on the system; and secondly, it is far, far too right-wing, because it totally fails to promote equality and fairness in the educational system.

If you know me, you'll not be massively surprised to hear that the second issue is where my personal bone of contention is to be found. Newsnight recently found the Swedish model to be unimpressive as a piece of pioneering social organization, noting that in recent years "not only are standards generally down, there are strong indications that the new schools have increased social segregation".

It seems to me blindingly obvious that this is precisely what you would expect from such a crude attempt to make the school system more dynamic.

Obviously, you won't hear me disagreeing with the Conservatives' statement that giving

many more children access to the kind of education that is currently only available to the well-off: safe classrooms, talented and specialist teachers, access to the best curriculum and exams, and smaller schools run by teachers who know the children’s namesis a good thing (although I might well dispute, based on personal experience and the teachers who I know, the claim that one only gets such attention in the public and private school system). And it's trivially true that opening more schools will improve class sizes and, assuming that their budget is not effectively reduced during this process, also improve teaching quality and time (we could look here to up-and-coming countries like China, where 7AM-6PM state-funded schooling is reality for many people, as Ken Livingstone pointed out earlier this week).

Of course,

The Swedish people generally approve of the new system. About 10% of all students of compulsory school age now attend the new schools, and in the upper secondary level it is about 20%.

In fact, the Conservatives' draft schools' manifesto has much in the way of increased spending recommendations and increased powers, intervention and supervision: they will

- allocate increased pay budget control for headteachers (allowing them to "pay good teachers more", rather than the converse, it seems implied);

- "pay the student loan repayments for top maths and science graduates for as long as they remain teachers";

- "legislate so that teachers can ban any items that cause disruption in the classroom";

- "reinforce powers of discipline";

- "set up technical Academies across England, starting in at least the twelve biggest cities";

- "fund 400,000 new apprenticeship, preapprenticeship, college and other training places over two years"

and so on. Hardly the anti-nanny state, fund-cutting image we're used to, is it? The point is the Conservatives are basically in favour of creating more schools and educational institutions and allocating more funds to the school sector. Sure, the usual pro-discipline measures are there, but what's that really but increasing how heavily then government intervenes in day-to-day life? (I'm not against it, but many Conservatives seem to claim to be.)

But really, the basic principle of allocating funds in an essentially market-controlled manner is going to do exactly what it does in every other market - create some really huge, bloated organisations (Tesco, Whitehall, I could go on), crows out many smaller specialist instutitions, and result in bizarre competitions that end up not being beneficial to student, or (more likely) teachers. Put in this light, the apparently reasonable approach of having

more unannounced inspections, and failing schools will be inspected more often – with the best schools visited less frequently [and] any school that is in special measures for more than a year will be taken over immediately by a successful Academy provider.

seems somewhat more likely to result in the rapid construction of very large, monocultured schools, with presumably the same old problems with discipline, management, class sizes, and inefficiency.

Surely this will result in 'good' schools (presumably judged by the local media as much as anyone more qualified) receiving far too many applications to cope with, and hence either taking in too many pupils to manage adequately, or turning away vast swathes of candidates (based on what, one wonders) who would be forced to turn to 'worse' schools, creating significantly more inequality in the educational system, in the short and medium term at least.

Impressively, the Conservatives appear intent on doing this without even offering a monetary incentives to the people owning the schools. Regardless, having schools compete for students might also make for a considerably more high-pressured environment, both for students and teachers.

And even the other celebrated Conservative goals (particularly of 'liberating' schools from the tyranny of the 'politicised' national curriculum) seem thin when you consider even their idols Sweden enforce their curriculum.

Also, an interesting comment is to be found in this draft manifesto - the Conservatives will

end the bias towards the inclusion of children with special needs in mainstream schools.

I don't know what everyone else makes of this, but it sounds fascinatingly dangerous to me.

is maximised (or more generally optimised) if and only if the actual

probability

of the event is exactly equal to the forecast probability.

is maximised (or more generally optimised) if and only if the actual

probability

of the event is exactly equal to the forecast probability.

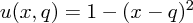

, where x is 0 or 1 according

to whether or not the event occurs and q is the estimated

probability it does. Then if the forecaster believes that there is a

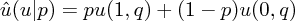

probability p that it does occur, the expected score (from his

point of view)

, where x is 0 or 1 according

to whether or not the event occurs and q is the estimated

probability it does. Then if the forecaster believes that there is a

probability p that it does occur, the expected score (from his

point of view)  is

is

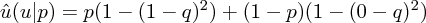

which is equal to

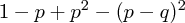

which is equal to  . So clearly, the

forecaster maximizes his expected payoff by setting his projected

likelihood q to exactly what he truly believes it to be, p.

. So clearly, the

forecaster maximizes his expected payoff by setting his projected

likelihood q to exactly what he truly believes it to be, p.

encourages forecasters to exaggerate (i.e. to pick q to be always

either 0 or 1).

encourages forecasters to exaggerate (i.e. to pick q to be always

either 0 or 1).

0 Comments